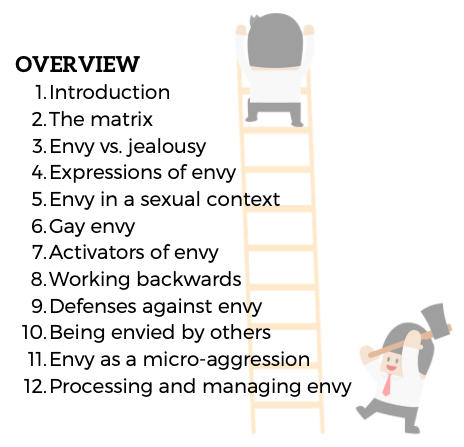

[log in to unmask]" style="color:inherit;text-decoration:none;display:inline-block;vertical-align:middle;margin-right:8px" target="_blank"> [log in to unmask]" style="color:inherit;text-decoration:underline" target="_blank">Rahim Thawer ∙ 23 min read ∙ View on MediumThe Matrix of Envy in Our Social and Sexual Lives Introduction We all experience envy. We feel envious when someone else possesses something we want or we wish we had. In these instances, being a have-not is probably hard to change, hence the tendency to get upset or suppress the emotion as much as possible. The object of your desire could be someone else’s achievements, their physical stature, friendship network, sexual prowess, or popularity. However, the desire to wantsomething is distinct from the experience of envy. Rather, the person in possession of the things or traits we desire becomes the target of our envy (Rodriguez Mosquera & Hurtado de Mendoza, 2010). As a psychotherapist, I think it’s important to talk about envy specifically because we’re often not allowed to: envy, after all, is a religiously and culturally sanctioned emotion. It can be helpful to explore whether envy triggers feelings of inferiority or a strong sense of injustice (particularly if you believe the person who possesses what you desire is undeserving or experiences systemic advantages). What’s confusing for many is the strong societal or cultural imperative to temper any sign of envy, despite our consumerist culture’s deep reliance on envy as a means of selling products and services and lifestyles. The shirt from your favorite designer doesn’t sell itself — the hot model you want to look like captures your attention and then gives you a false promise to be them, for a price. In the therapy room, we can illuminate that unarticulated psychic relationship (and phantasy) about you and the model to “treat” the potentially destructive sequelae of envy. The Matrix Envy activates a matrix of affective orientations (meaning “many kinds of moods and emotions”). It can feel hard to talk about the matrix of envy even when we give ourselves permission and attempt to erode the stigma. Nevertheless, envy operates in our social and sexual lives with the same frequency as basic anxiety. Consider your level of agreement with the following statements (adapted from Lang & Cruise, 2015) as a starting point to explore your own relationship to envy.

Regardless of your level of agreement with these statements, I’m certain that they each evoked a range of feelings. This is precisely the matrix of envy that I now want to explore with you.  Envy vs. Jealousy If you’ve ever said, “I’m jealous of that person’s salary,” you’ve mistaken envy for jealousy. Envy and jealousy are distinct experiences with some overlap. Envy emerges in the context of two people whereas jealousy involves a third. I often think about jealousy as a reaction to the threat of losing somebody. When you are in a romantic relationship and your partner begins to devote once protected time and affection to someone else — another partner, a co-worker, an ageing parent — you might feel like that third party is responsible for taking something from you. Beyond romantic relationships, jealousy also shows up in early childhood (or in adulthood for that matter) when a parent/teacher/employer gives more attention/praise to one child/student/employee over another. In each of these examples of jealousy, we’re talking about something we already possess (some kind of relationship) that feels threatened by a third person. Jealousy sometimes invites a tempting opportunity to intervene with the third person through disruption, deception, controlling behaviour, or expressions of anger. Of course, this type of “acting out” is often frowned upon socially (because it’s accurately labeled as manipulation), and in some cases, constitutes emotional abuse. The signs of jealousy are visible and more easily identified than those of envy. Let’s return to the example of a romantic relationship. If I compare myself to the person to whom my partner is attracted, that’s where envy comes up. When I experience envy, I’m immediately thinking about something I lack or wish I had, which takes me to a place of sadness and grief. The comparative function of envy makes it a two-person (dyadic) phenomenon, while jealousy involves a third (triadic). In order to define envy, psychoanalyst Melanie Klein (1957) draws on its association with greed and its roots in the earliest relationship with one’s caregiver: [Envy is] the angry feeling that another person possesses and enjoys something desirable — the envious impulse being to take it away or spoil it. Moreover, envy implies the subject’s relation to one person only and goes back to the earliest exclusive relation with the mother….One essential difference between greed and envy, although no rigid dividing line can be drawn since they are so closely associated, would accordingly be that greed is mainly bound up with introjection and envy with projection. (p. 181) Expressions of envy Some people experience benign envy — a kind of “frustrated desire” — while others experience malicious envy (Lang & Crusius, 2015). I often identify malicious envy in my patients (and myself) when it can be described as sitting in the pit of your stomach as you start to feel hostility, shame, sadness, and resentment. Altogether, envy is a highly embodied emotion (akin to a physical sensation), yet, unlike joy or sadness, it doesn’t come with a universal facial expression because it’s often so well disguised. If envy didn’t have a malicious component to it, it wouldn’t be considered a deadly sin in Christian theology. From Shakespeare’s Othello (1603) to Gossip Girl (2007), our society reminds us regularly that envy can lead to destruction of some kind: destruction of the self, the other, or of social relationships. However, these cautionary examples don’t consider benign envy that is often fleeting or even motivating. While English and Spanish have only one word for envy, the benign-malicious distinction is made more explicit in German and Russian (Lang & Crusius, 2015). We know that envy is experienced across cultures and arises in the context of social comparison. Episodic envy is what most of us would be able to admit most readily; that is, feeling envious of someone else’s attributes, status, or skills in a specific setting or in the context of a particular incident (Cohen-Charash, 2009; Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2017). Dispositional envy, by contrast, is more difficult to manage (and admit to) because it entails a person experiencing a sense of inferiority more chronically, and then uses competition and comparison as a conceptual tool to navigate the world and nearly all relationships (Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2017; Rentzsch & Gross, 2015). If you experience dispositional envy, you’re likely in a lot of emotional pain. It also means that you are probably in touch with your own experiences of shame. Delving into the [log in to unmask]" style="color:rgb(51,51,50);text-decoration:underline" target="_blank">nuances of shame might be a useful starting place for self-exploration and healing. Envy in a sexual context What are things we can be envious of in a sexual context? You may be in awe, and slightly envious, of people you know who have been able to maintain a long-term relationship through good times and bad. I’m sure we have all met that couple that seems to have negotiated the terms of their long-term open relationship effortlessly while being fiercely committed to one another. They look like a superhero team when they’re out in public and the one you happened to have slept with sings the praises of his partner as post-coital pillow talk. They’re obnoxious! No, wait. I’m just envious. Maybe you feel envious of the number of partners others have, or the frequency of their sex. Maybe you’re in a relationship and you envy others’ singleness. And who isn’t envious of at least one other person’s physical features? Here’s a unique one: being envious of other people’s ability to engage in sexualized drug use; envious that they can use drugs and pair that activity with sex when you are more risk averse or have a lower tolerance for substances. Are you envious of people’s sexual networks and communities, someone’s sexual CV? Perhaps you’re envious of other people’s sexual fluidity, that they’re able to be with multiple people and multiple genders, and you wish that was you. Or maybe you’re envious of other people’s partners because they just seem to be more open-minded and willing to try the things that you wish your partner would be willing to do. Is it others’ bravery or sense of adventure that leaves you feeling green? I facilitated a workshop recently in which a participant stated they experience envy of people who don’t have to deal with the aftermath of childhood trauma in their sexual encounters. For the person without such a history, beyond consent, no further discussion of triggers and possible dissociation is required.  Gay envy Do you envy someone’s access to sexual spaces? As a cisgender gay man, I can go to a sauna or a bathhouse where guys have anonymous sex. I know some of my trans masculine friends have been envious of my ability to access those spaces. They might be thinking, “Hey, that would be fun and if I were able to participate in that space, there would be emotional rewards for my masculinity, my gender experience. And, it’s an unfair that it’s not as readily available to me!” I’m also thinking about the currency of gym bodies and online profile photos in gay culture that attract all the taps, woofs, and swipes a sister could ask for. I’ve had the experience of hanging out with friends and just as we’re about to part ways each of us quickly logs into Grindr — naturally. We’re either looking for the next thing or feel like we’d be remiss to not make ourselves at least visible on the fresh grid of thumbnails in that new neighbourhood (that’s just a few kilometers away from home). I almost always peek over at the other person’s phone and on so many occasions have thought to myself, “Hey, what the heck? How come they’ve got so many unanswered messages, so many taps?” In truth, anytime I’ve had more than three conversations going simultaneously, I’m immediately overwhelmed and unsure of where to invest my time. Yet when I look at someone else’s busy grid, I’m not overwhelmed on their behalf. I’m envious. Has a gay man ever told you a story about spontaneous sex where one of the partners was just ready to bottom without any notice? How do these people have so much control over their digestion and the confidence to bend over at a moment’s notice? Being a receptive partner for anal sex is just so fun. I’m envious of guys who can do it easily, for a long period of time, and with multiple people in a week. This begs the question: what exactly is it that I want that they possess? Perhaps it’s sexual availability, versatility, confidence, or the absence of anxiety. Ask yourself: How does envy interact with your sexuality and sexual experiences? Does envy of others motivate you to do things differently for yourself? Does your envy make you feel inferior and immobilized? When I consider my own experiences of envy in the context of relationships and sex, it’s almost always in this amorphous space before I know a person that I presume they possess a superhuman sexual prowess. This is because envy is fuelled by fantasy and imagination. Once you know about the other person’s mundane life, your envy starts to fade. Nevertheless, let’s say I’m online and swiping my life away looking for the right matches. If I see people who have attributes that I don’t possess, that I feel envious of, behind the screen of my phone, I certainly feel more emboldened to send them a tap or swipe right. Screens provide a solid emotional cover. And who knows? Maybe they’re into me too. If I can disrupt the compulsion demanded by the app, I try to ask myself: do I actually want to meet this person if they swipe back? Or, is this an exercise in confidence and conquest? Or perhaps an exercise in low self-esteem and self-fulfilling prophecies? When we’re searching for mates online, I can’t help but wonder: does the low stakes virtual space allow our envy to become unruly? Behind a screen, we might allow ourselves to be more adventurous and bite that lower lip with interest more than we would ever do in person. However, desire isn’t the problem here. Rather, it’s more the exhaustion of desire — when it’s specifically driven by envy — that leads to the casting of a wide net for partners, which in turn means being vulnerable, engaging with the reality of your superficial envy, and managing endless rejection. In the last decade of working in queer men’s health, there have been many clinical issues and programmatic topics that have come to the surface on the teams and in the boardrooms where I’ve sat: homophobia, HIV stigma, internalized racism, sexualized drug use, depression, isolation, suicidality, body image, and shame. I’ve never heard a conversation about the role of envy in our lives as queer guys. Many of us grow up experiencing envy around masculinity at an early age. We’re envious that other boys fit in and get celebrated easily. Many gay men have told the story about a straight friend they fell for early in their coming out process. I’d speculate that it was less about love and more about envy: “I want to be you, but I’ll settle for possessing your straight-passing advantages by proximity to you!” If this is true — that envy is a critical feature of gay men’s lifespan development — we urgently need to examine its trajectory as our individual and community interventions will fall short in its absence. There’s a thriving party n’ play subculture (also known as chemsex) in gay men’s communities in many countries around the world. PnP can refer to sexualized drug use with any number of substances being used to facilitate and enhance sexual encounters. The substance that draws most attention is crystal methamphetamine for its addictive qualities. From a lifespan development perspective, I’d suggest that the desire to parTy gets its wings from creating a space where envy and shame can be mitigated or completely erased. That is, a celebration of many masculinities and unlimited intimacies can be accessed without the painful judgements or comparisons embedded in our social world. Activators of envy Different factors are going to trigger your experience of envy in social and sexual settings. Envy, like shame, is a social emotion. It doesn’t just occur in a vacuum. If I feel envious, it’s inherently in relation to someone else. Consequently, envy is often activated when we observe:

In a way, these are all narcissistic injuries — perceived slights against our self-image. This is about feeling overlooked, ashamed, or inferior. For some people, envy can arise in specific contexts, e.g., being in a classroom and sharing an answer, only to listen on as somebody else with whom you feel a kind of competition, shares a slightly better answer. Any interpersonal context where you feel inferior or ashamed, out-performed, sidelined, overlooked — those are situations where you might be experiencing a narcissistic injury (or wound). Are people with narcissistic personality disorder more likely to experience dispositional envy and therefore more regular slights? Possibly. Yet it makes no sense to downplay injuries that have not received such a diagnosis. We all experience narcissistic injuries and they are an important part of matrix of envy that needs to be examined. Working backwards If you have difficulty identifying the contexts that activate your envy, you may need to work backwards. For example, one of the ways I know that I’ve been envious is when I notice my own schadenfreude (by now you’ll notice the English language is lacking serious nuance), the German word denoting the experience of finding pleasure in someone else’s suffering or humiliation. In some contexts, the signal may be noticing your sadism when you’re sprinkling salt on someone’s wound with an “I told you so.” A common experience that rarely gets talked about is seeing a person you know who is normally drenched in privilege finally having a tough time in life. You’re unlikely to be outwardly joyous about their suffering, but you might register it as a leveller of the playing field, which, in turn, brings you some personal satisfaction. Shadenfreude and sadism aren’t the only diagnostic criteria for envy. They can also be a reflection of your disowned parts as seen in another person. Think of a individual (or a television character) you despise. Consider what specific qualities they possess that make you cringe. Think about how much you wish you could smack them and “turn off” the parts of them that really bother you. That’s your sadism (desire to punish) — it wants the other person to feel some pain so they will change. Just like you did. What you dislike in them is in fact a mirror of the parts of you that you disowned at an early age because they didn’t fit with your survival strategy at the time. Now, they arouse an anger or pity in you that conceal your underlying envy (Terry, 2014). In sum, sadistic pleasure (Rosenberger, 2015) and schadenfreude can be signs that you’ve encountered someone who possesses attributes that are connected to one of your disowned parts. And, you though you don’t like them or enjoy seeing them suffer, you also envy them on some level. Another way to work backwards is to notice your sense of competition as an indicator of envy’s presence. Here’s an example: Let’s say I’m invited to a house party — it’s the pre-game before a group of us go to the bar. I’ve been invited by my friends. But when I show up, I realize most of these guys are white. I think, “okay, whatever, I’m here doing my thing, I’m going to pour myself a drink.” I see another South Asian person and he’s talking to a couple of really cute white guys. I immediately become flushed with both jealousy and envy. This is just how envy, white supremacy, and internalized racism operate in the real world. I feel competition with the other South Asian person for the attention of the white guy. I experience the white person’s attention and gaze toward the other person who looks like me as a narcissistic injury. It’s not lost on me that my experience of episodic envy reifies the racist idea of people within a racial group being seen as “the same”; still, the sense of competition is indicative of my envy. Defenses against envy How do you protect yourself–or defend against–the experience of envy? After all, there isn’t a recommended script for how to deal with or articulate your envy in a way that would be helpful to you or others around you. Defenses are just things that we do, sometimes subconsciously, to put some distance between us and another feeling that is hard to tolerate. So, what do you do? Do you take up more space? Do you shrink yourself to be less visible? Do you dance in the center of the room? Do you drink more to help you feel unaffected by anything? And why do we summon defenses against envy? Well, if we sat with it, we’d have to accept that we might be lacking something and then we’d either be grieving or endlessly re-evaluating our values. For example, if I’m envious of my friend who has muscular arms and earns twice my income and I’m to simply sit with it, I’d be grieving. If take the time to I re-evaluate my values, I may begin to counter-identify with the culture that celebrates his progress and teaches me to use it as a measuring stick. Admittedly, a defense can also be quite adaptive. If I can challenge the call to compete and not get sucked into my own shame, I can think about my own strengths and simply be curious or enamored by someone else’s. Envy, in other words, activates a web of affective orientations — many of them defense mechanisms — to help us cope with this feeling we want to rid ourselves of. Based on my observations as a therapist and introspection in my own life, here are all the things that I’ve seen come up:

What does your matrix of envy look like? What does your matrix of envy look like?In many ways, envy and shame are intimately connected. Envy of someone’s relationship status can activate shame about being single. Envy makes you aware of what you don’t have access to and throws you into a grief cycle. Let’s return to internalized racism and the online hookup scene. Let’s say I’m logged in to Grindr and though I’m not looking for anyone in particular, my swipes and taps lean heavily toward men who are tall and white. How awful to go from tacit to explicit awareness about structural envy and, by extension, internalized shame? The way envy operates here is stifling because I’m grieving all the things I’m not while also de-sexualizing other people who look like me (I don’t hate myself as much as my examples suggest, I swear!). When a meeting is eventually arranged with an appropriate suitor, if it’s envy and shame that have driven me to this encounter, how can I even focus on being present and enjoying sexual pleasure instead of being caught up in performance anxiety? Being envied by others What does it feel like to be envied by others? How do you know when it’s happening and does it make you uncomfortable? In all honesty, I’m not sure when I’m being envied, but I do know that I have been. Most of us likely have been envied at some point. We all possess something another person wishes they had (more of): attractiveness, intellect, status, money, style, clothing, popularity, and so on. Have you considered how many of your friendships might have begun because one or both parties were slightly envious of the other? In these cases, mere proximity can quell the aggression of envy and turn it into something else. Envy, in other words, can certainly breed hostility and contempt, but that’s not always, or necessarily, the case. Given that when we experience envy, our defenses may range from seeking proximity to the destruction of the other person, it’s unsettling to consider that someone’s envy of us is constantly permeating their motivations to be nearby. Being envied can come with a myriad of responses and consequences:

In my culture, I was taught that there is joint responsibility to prevent the consequences of envy — or nazar, which translates as `someone else’s gaze.’ It’s commonly believed that “showing off” can attract someone else’s negative gaze, which can then hamper your growth. Having contempt for someone else’s gains or possessions is discouraged and people also use amulets, dark eyeliner, and attributions to a higher power to deflect others’ envy. In the milieu of popular culture (read: Instagram mental health memes), we tend to be told that we should wholly accept a compliment without deflection or false modesty — to own our achievements and to publicly celebrate our worthiness. Despite the different types of socialization, people often respond to a compliment or redirection to an object of potential envy (wealth, accolades, possessions) by somehow depreciating its value: “Yes, the high GPA is great but it cost me so many nights of sleep!” or “My director’s salary is nice but you won’t believe the amount of admin it comes with!” or “We’re happy to have found this home but the bank owns most of it!” [I feel you need to finish this point — there’s this inclination, and so now it relates to envy how…]  Envy as a micro-aggression So far, I’ve explored envy in the context of everyday interpersonal relationships, and when there is an imbalance of systemic power that favors the target of envy. But what happens when a person from a dominant group (one with historical and societal power) envies a someone from a target group (one with historical and societal disadvantage)? I’d argue that it’s sometimes experienced as a micro-aggression, especially if there is a false presumption of unfairness. In their paper, Clark, D. et al (2014) explored Indigenous students’ experiences with racial micro-aggressions in Canada and identified that these students were often the targets of envy due to a presumption of tax and tuition subsidies that they either received or for which they might be eligible. Why does the feeling of envy operate as a micro-aggression? The projection of “not having” by non-Indigenous students discounts the historical events and the foundations on which such policies and programs for equal opportunity are built. In a similar vein, I’ve had some of my white therapy patients talk about their envy of certain social justice activists, in particular Black and brown folks who have gained notoriety (sometimes in the form of a large social media following). It’s not a malicious envy but it does come with the complexity associated with processing their own narcissistic injuries in the arena of activism. A more extreme example of this would an able-bodied athlete (let’s call her Joan) being envious of athletes with disabilities. Sound bizarre? Well, there are two explanations for this actual occurrence. The first is that Joan is grieving the loss of the centre-stage (an entitlement) that comes from being ascribed a privileged social position. The second possibility is that Joan has a phantasy about being seen as an inspiration to others and she imagines that she’d receive more love or attention if she was understood as successful despite living with disadvantages (this is rooted in a childhood conflict, no doubt). She wants people to know she’s that good. Either way, her grievance, narcissism, and envy play out as micro-aggressions. An athlete living with a disability likely had to fight against being reduced to inspiration porn regularly and would find the external romanticizing of their struggle as offensive. Processing and managing envy You experience envy, but now what? And, I told you it’s normal, so should we just move on? No. Talking about envy and all its dimensions should help us understand it better. With any luck, we can also reduce its stigma. Once we’re primed and ready, we can actually begin considering what processing and managing envy might include. First, you need to identify if your experiences of envy are episodic or dispositional. It might be one or both. If your answer is `neither,’ your denial may be protecting you until your mind and body are more prepared for this conversation. Next, consider if your experience of envy tends to be benign or malicious. If it’s malicious, don’t jump to self-criticism — that will only activate your shame and replace one emotional wound with another. Ask yourself, when it comes to both the object of desire and your target of envy, what is your endgame? Rosenberger (2005) suggests that the aim of envy is to either acquire (possess) or destroy (sadism). If you want to harm someone or see them fail, that will likely create more misery for you because constant comparisons and glimpses of their success will consume you. If, instead, you say, “I want to be able to experience gratitude for what I have and legitimate rage for what isn’t within reach for me,” that’s much more reasonable. My strong recommendation is to create space for both the positive and negative and work on containing each. Too much of either and you lose the authenticity of your experience in the world. Some targets of your envy such as celebrities, will always remain at the distance. However, there are others with whom you might want to have a conversation. Talking about a stigmatized emotion like envy might feel like opening a wound to selectively allow its toxicity to exit peacefully from your body. (Of course, having a conversation also depends on the other person’s temperament, If the object of your envy is a sadist, this kind of opening would probably back-fire). What is a good way to invite a close person, family, friend or lover to speak about envy?

Again, envy isn’t necessarily destructive. With self-awareness and some emotion regulation skills, envy can become a communicator and diagnostic tool. It will reveal to you exactly what a toxic world has taught you, and then, armed with those insights, you can decide if the drive to possess what someone else has needs to be extinguished or pursued with caution.  REFERENCES Brooks, A. W., Huang, K., Abi-Esber, N., Buell, R. W., Huang, L., & Hall, B. (2019). Mitigating malicious envy: Why successful individuals should reveal their failures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(4), 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000538 Clark, D. A., Kleiman, S., Spanierman, L. B., Isaac, P., & Poolokasingham, G. (2014). “Do you live in a teepee?” Aboriginal students’ experiences with racial microaggressions in Canada. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(2), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036573 Cohen-Charash, Y. (2009). Episodic envy. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(9), 2128–2173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00519.x Fam, J. Y., Yap, C. Y., Murugan, S. B., & Lee, T. (2020). Benign and malicious envy scale: An assessment of its factor structure and Psychometric Properties. Psychological Thought, 13(1), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.37708/psyct.v13i1.389 Klein, M. (1988). Envy and gratitude, and other works, 1946–1963. Vintage. Navarro-Carrillo, G., Beltrán-Morillas, A.-M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2017). What is behind Envy? approach from a psychosocial perspective / ¿Qué se esconde Detrás de la Envidia? aproximación desde una perspectiva psicosocial. Revista De Psicología Social, 32(2), 217–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2017.1297354 Rentzsch, K., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Who turns green with envy? conceptual and empirical perspectives on Dispositional Envy. European Journal of Personality, 29(5), 530–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2012 Rodriguez Mosquera, P.M., & Hurtado de Mendoza, A. (2010). I fear your envy, I rejoice in your coveting: on the ambivalent experience of being envied by others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; 99(5):842–54. doi: 10.1037/a0020965. Rosenberger, J. W. (2005). Envy, shame, and sadism. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 33(3), 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.2005.33.3.465 Terry, P. (2014). Beware of pity which conceals envy. Psychodynamic Practice, 20(3), 280–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753634.2014.916842 Medium, 548 Market St, PMB 42061, San Francisco, CA 94104 Careers·Help Center·Privacy Policy·Terms of service |